When one speaks about diseases that have influenced the trajectory of human history, two terms often come up: epidemics and pandemics. But what are they, exactly? An epidemic refers to an increase in the number of cases of a particular disease in a specific population or region, often surpassing what’s typically expected. On the other hand, a pandemic is an epidemic that has spread over multiple countries or continents, affecting a more considerable number of people.

The distinction is significant. All pandemics start as epidemics, localized outbreaks that, under certain circumstances, manage to cross borders and seas. It’s when these epidemics spread and multiply in new territories, often facilitated by factors like trade, travel, or sheer chance, that they metamorphose into pandemics.

Now, why is this differentiation crucial? Well, understanding how an epidemic can escalate into a pandemic is paramount for public health measures. Many epidemics can be contained locally, but if left unchecked, their reach can be global. The history of humanity has seen its share of these instances, some more harrowing than others. This leads us to our main exploration today: the 10 most devastating epidemics and pandemics in history.

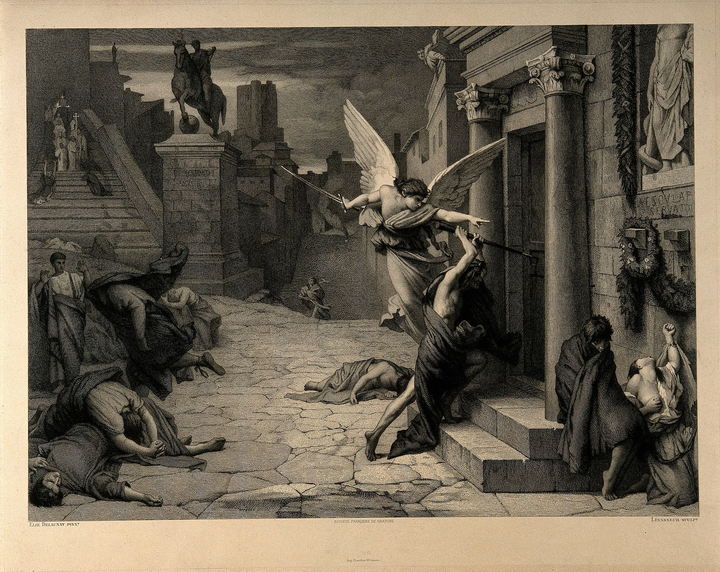

10 – The Plague of Cyprian: A Frightening Era

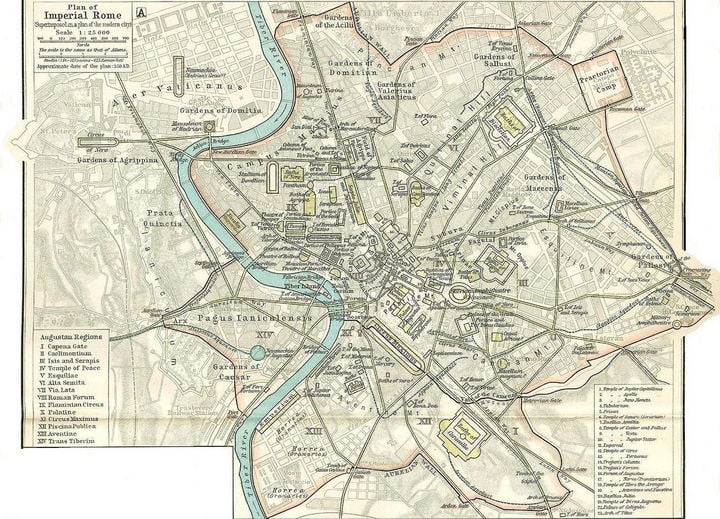

In the midst of the 3rd century AD, the Roman Empire faced a terrifying health crisis, known today as the Plague of Cyprian. Named after St. Cyprian, a bishop who documented its devastating effects, the outbreak remains an integral part of pandemic history.

The exact origins of this plague remain a subject of debate. Some historians suggest it originated in Ethiopia, spreading through Northern Africa, then crossing the Mediterranean, reaching Rome. As for its spread, the dense urban populations of the Empire, coupled with expansive trade routes, likely facilitated its dissemination.

The symptoms described, including diarrhea, vomiting, and gangrene of the extremities, have led some to speculate that it might have been a form of Ebola or another hemorrhagic fever. Its impact was calamitous; in some cities, the death toll was so high that it’s said the living couldn’t keep up with burying the dead.

Ending this outbreak was more a matter of time and natural progression than medical intervention. As more individuals contracted and recovered from the disease, community immunity began to rise. Additionally, changes in trade patterns and urban dynamics might have disrupted its spread.

Historically, the Plague of Cyprian had broad implications. The Roman Empire, already facing political and economic instability, was further weakened, making it susceptible to external invasions. Moreover, as communities struggled, Christianity gained prominence, with its followers often at the forefront of care during these dire times.

09 – The Plague of Athens: Democracy’s First Test

Around 430 BC, Athens experienced a plague that would challenge the very tenets of its blossoming democracy. The Plague of Athens, which hit during the early years of the Peloponnesian War, is a historical plague that still intrigues scholars today.

Originating most likely from sub-Saharan Africa, the disease entered Athens via its bustling port, Piraeus. Considering the wartime naval blockade, citizens from the countryside took refuge within the city walls. This sudden population surge led to overcrowding, creating an ideal breeding ground for disease transmission.

The disease’s symptoms, as described by historian Thucydides, included fever, bloody throat and tongue, and skin lesions. While its exact nature remains speculative, possibilities range from typhus to measles.

Though Athens had no means to medically curb the outbreak, its eventual decline probably came due to increasing immunity among survivors. However, before that respite, nearly a third of the Athenian population succumbed to the disease.

The Plague of Athens wasn’t just a health disaster; it reshaped Athenian society. Trust in the democratic leadership eroded, leading to political upheavals. Additionally, traditional religious beliefs were questioned as temples became ineffective sanctuaries against the disease.

08 – The Antonine Plague: A Blow to the Roman Might

Between AD 165 and 180, the Roman Empire came face to face with a silent adversary: the Antonine Plague. An early encounter in the annals of global pandemics, this outbreak challenged an empire that seemed invincible.

The disease was believed to have been brought to Rome by soldiers returning from campaigns in the Near East. Rapidly, it permeated the vast Roman territories, exploiting the interconnectedness of Roman roads and trade routes.

Historical accounts, especially those by the physician Galen, describe symptoms reminiscent of smallpox or measles. Fever, sore throat, diarrhea, and, in later stages, skin eruptions were common. The death toll reached staggering proportions, with some estimates suggesting over 5 million fatalities.

While medical knowledge of the time was inadequate to tackle the disease head-on, its gradual decline might be attributed to increasing herd immunity and possibly changing environmental factors.

The Antonine Plague had long-term repercussions for the Roman Empire. With significant military losses, border defense became more challenging, opening gates for barbarian invasions. The deadliest plagues like this one also altered the socio-economic landscape, leading to labor shortages and emphasizing the need for external recruitment. The Empire’s very ethos underwent a transformation, paving the way for internal reforms and shifts in external relations.

07 – The Great Plague of London: Darkness Over The Thames

In the mid-17th century, one of the most infamous plagues in history emerged from the shadows, casting a somber veil over London: the Great Plague of London. This devastating event serves as a haunting chapter in pandemic history.

Starting in 1665, this bubonic plague made its way to London’s doorstep via trading ships. The fleas on rats, unbeknownst to the residents, were the primary carriers of this menacing disease. London’s cramped living conditions, with narrow alleys and poor sanitation, provided a fertile ground for the rapid spread of the disease.

Characteristic symptoms included painful buboes or swellings, fever, and eventual delirium. Within a week, many victims would succumb to the relentless disease. Historical records estimate that nearly a quarter of London’s population was wiped out.

Despite their limited medical knowledge, officials took measures like quarantining affected houses. With the onset of winter, the fleas died, leading to a decrease in cases. By 1666, the plague gradually receded, leaving a city scarred and forever changed.

The Great Plague of London not only devastated lives but also led to significant changes in medical practices, urban planning, and public health policies. It is a stark reminder of nature’s unpredictable wrath and humanity’s resilience.

06 – The Plague of Justinian: Byzantium’s Despair

The Byzantine Empire, at the zenith of its power, was confronted with a nemesis that shook its very foundation: the Plague of Justinian. As one of the worst pandemics in history, its impact on the empire’s political and economic structure was profound.

Emerging in 541 AD, historians believe that the disease, much like the Great Plague of London, was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacteria, transported by fleas on black rats. These rats made their entry into Constantinople, the Byzantine capital, through grain shipments from Egypt.

The symptoms mirrored other historic diseases caused by the bubonic plague, with fever, chills, and swollen lymph nodes. The rapidity of its spread and the high mortality rate, with deaths in the thousands per day at its peak, were staggering.

Though it ebbed and flowed, the plague persisted for over two centuries, leading to recurring outbreaks. Population decline due to the disease greatly weakened the Byzantine military and economy, making them vulnerable to enemies like the Lombards and Persians.

Yet, as with all things, the Plague of Justinian eventually faded, possibly due to increasing herd immunity and changes in climate and trade patterns. Its legacy, however, remains a testament to the vulnerabilities even the mightiest empires face.

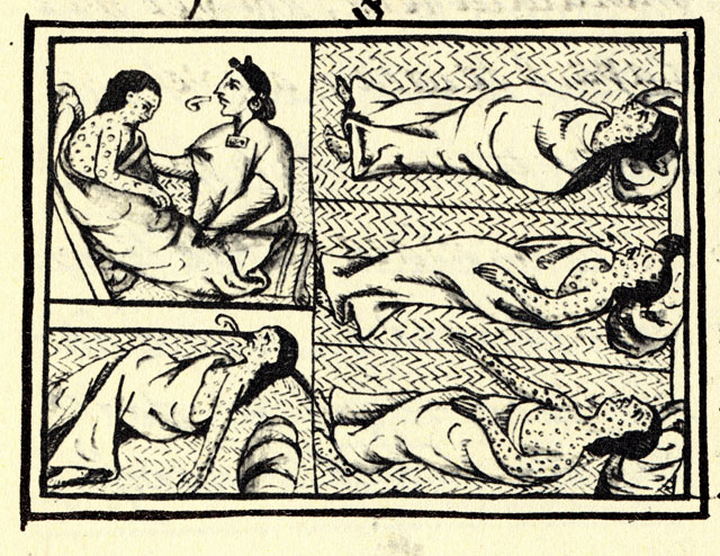

05 – Cocoliztli Epidemics: Mesoamerica’s Silent Scourge

Mesoamerica, known for its vibrant civilizations like the Aztecs, witnessed a series of epidemics in the 16th century that remains somewhat enigmatic: the Cocoliztli epidemics. Unlike many historical plagues that have known origins, Cocoliztli’s cause remains subject to speculation.

Starting in the 1540s, shortly after Spanish conquest, these epidemics were different from other diseases brought by Europeans. Symptoms included high fevers, headaches, bleeding, and jaundice, leading to a rapid decline in the patient’s health.

Given the absence of contemporary medical records matching the symptoms, the exact cause is still debated. Some researchers suggest it might have been a native hemorrhagic fever, while others argue it could be related to conditions like salmonella.

The Cocoliztli epidemics decimated indigenous populations, with mortality rates reaching up to 90% in some areas. The social fabric of these grand civilizations unraveled quickly, leading to a power vacuum that was eventually filled by Spanish settlers and their allies.

The lasting impacts of these epidemics can be felt even today. They reshaped the demographic landscape of Mesoamerica, paving the way for European dominance and influencing the socio-cultural evolution of the region for centuries to come.

04 – Great Plague of Marseille: The Siege of France’s Port City

In the tapestry of historic diseases, the Great Plague of Marseille stands out as an ominous thread, symbolizing the fragility of interconnected societies. Europe’s last significant bubonic plague began its grip on Marseille, a bustling French port, in 1720.

Originating from a cargo ship called the Grand-Saint-Antoine, which had traveled from the plague-infected Middle East, the disease found an easy conduit in the unsanitary conditions and close quarters of the city. Symptoms typical of the bubonic plague—swollen lymph nodes, fevers, and chills—became all too common sights.

Desperate to contain its spread, officials erected plague walls and enforced stringent quarantine measures. Yet, the pestilence moved with alarming rapidity, soon engulfing other parts of France. By 1722, the plague had claimed over 100,000 lives.

But as with previous plagues in history, the resilience of the human spirit shone through. Gradual advancements in medicine and better quarantine methods began turning the tide. By 1723, the Great Plague of Marseille dwindled, leaving a populace that was more aware and prepared for future health threats.

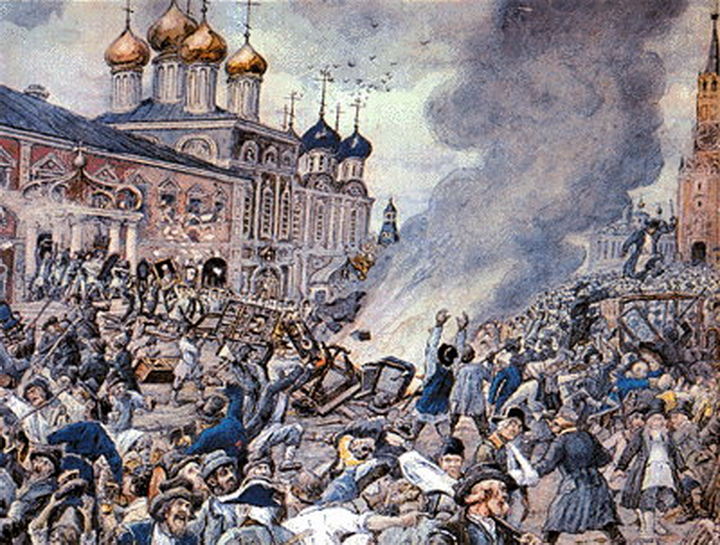

03 – The Russian Onslaught: Plague of 1771

Russia, a land of vast landscapes and resilient people, was not immune to the scourge of global pandemics. The Plague of 1771, part of a broader epidemic wave, stands as a testament to the social and political upheavals diseases can induce.

The disease entered Moscow in 1770, brought by soldiers returning from the Ottoman front. As pandemic history has often shown, crowded living conditions and rudimentary medical knowledge exacerbated the spread. Symptoms of high fever, delirium, and painful boils soon became common.

The plague ignited more than just health fears; it set off socio-political unrest. With an overwhelmed health system and rising death tolls, public discontent grew. The situation reached its climax with riots in Moscow, showcasing the profound societal impacts of such deadliest plagues.

Civic response, combined with the onset of winter, gradually curtailed the disease’s spread. By 1772, the plague retreated, leaving behind a transformed socio-political landscape and lessons on public health importance.

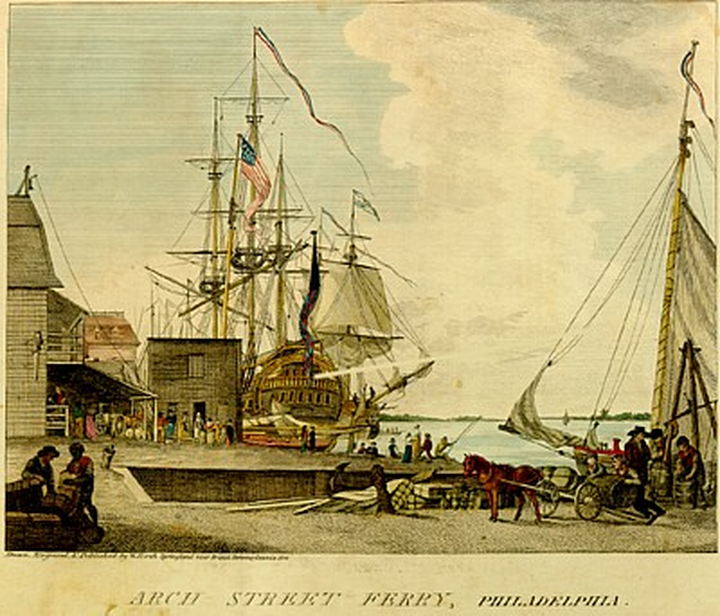

02 – The American Woe: 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic

America’s tryst with epidemics presents numerous chapters, but the 1793 Philadelphia Yellow Fever Epidemic remains particularly poignant. As the then U.S. capital, Philadelphia was unprepared for the disaster brought on by this mosquito-borne disease.

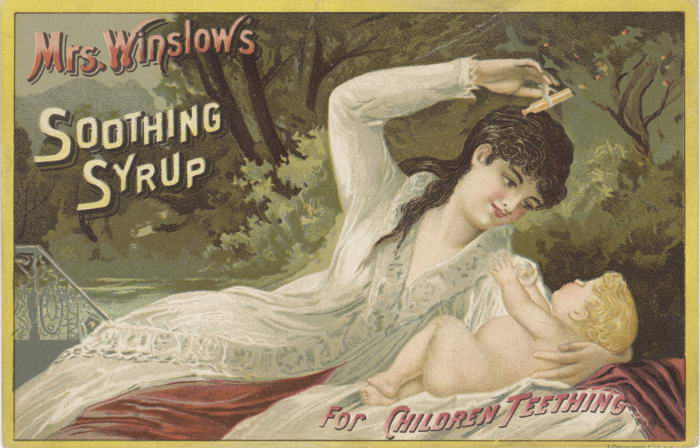

Yellow fever, unlike other historical plagues, has a distinct onset. Victims experienced fever, jaundice (leading to its name), and even internal bleeding. The Aedes aegypti mosquito, carrying the virus from infected to healthy individuals, became the inadvertent Grim Reaper.

With thousands succumbing to the disease and no knowledge of its mosquito transmission, panic was rampant. Many fled the city, including government officials, leading to a near-complete breakdown of governance.

Yet, as the annals of pandemic history have shown, resilience and human adaptability eventually shine. The first frost of the season killed off the mosquito population, effectively ending the epidemic. The episode served as a crucial catalyst for improving sanitation and health infrastructure in American cities, setting the stage for better public health systems.

01 – The Black Death: Humanity’s Darkest Hour in Pandemic History

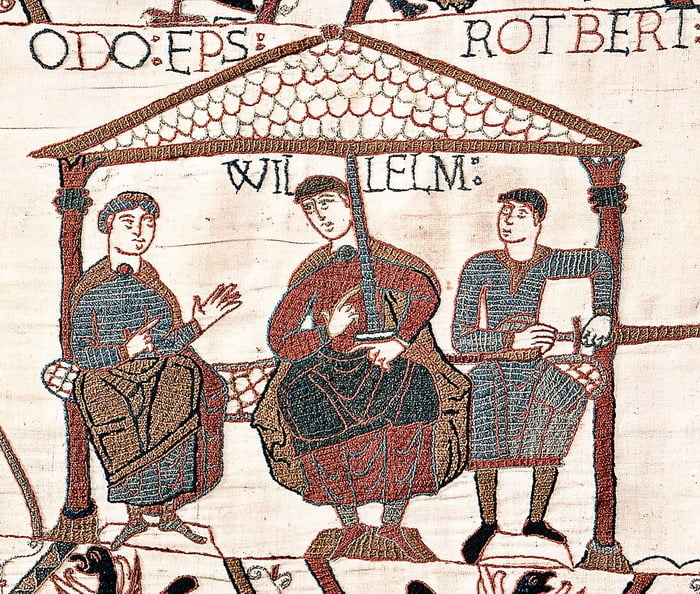

Few historical plagues are as deeply etched in collective memory as the Black Death. Emerging in the 14th century, this bubonic plague reshaped civilizations and took an estimated 75 to 200 million lives, accounting for nearly a third of Europe’s population.

It began in Central Asia and, carried by Silk Road merchants and their fleas-infested rats, reached Crimea. From there, it swept across Europe with unparalleled fury. Manifesting as painful, swollen lymph nodes or “buboes”, followed by fever and chills, the plague earned its chilling moniker.

The socio-economic impacts were profound. Labor shortages from the staggering death tolls led to rising wages, and the old feudal system began to crumble. It marked the end of an era and paved the way for Renaissance, a period of renewed interest in art and science.

Yet, the Black Death wasn’t a singular event. It recurred several times until the late 18th century. However, improved public health measures and a better understanding of its transmission helped contain and eventually diminish its impacts. This devastating plague’s legacy is a testament to human resilience, adaptability, and our ever-evolving understanding of diseases in the face of deadliest plagues.

Conclusion: The Spread and Termination of Epidemics

Diseases spread through a myriad of channels. These can range from person-to-person contact, contaminated water or food, respiratory droplets in the air, or even via vectors like mosquitoes. As our global connectivity has increased, so too has the potential for rapid disease spread. International travel and trade, population density, and changing land use patterns can all facilitate the transmission of pathogens.

So, how does an epidemic conclude? In historical contexts, an epidemic typically ended in one of two ways: either a substantial portion of the population became immune to the disease (through infection and recovery), or the disease was effectively contained and eradicated through medical and public health interventions. In more modern times, the development and distribution of vaccines play a significant role in halting the spread of diseases.

As we reflect on the historic diseases that have marred human history, we’re reminded of the importance of understanding disease transmission and the measures that can prevent or mitigate its impact. This reflection is even more crucial in a world where global pandemics, like COVID-19, remind us of our vulnerabilities and interconnectedness.

The Ripple Effects: How Pandemics Impact Societies

Pandemics, beyond their immediate health implications, have profound effects on societies. The aftermath of a major outbreak can ripple through every sector, from the economy to politics, from art to religion.

Firstly, economies often take severe hits during pandemics. Trade can come to a standstill, businesses may shutter, and unemployment can skyrocket. For instance, during the Black Death, labor shortages led to increased wages for workers, while simultaneously, the cost of goods soared.

Socially, pandemics can accentuate inequalities. Those in lower socio-economic groups often suffer disproportionately, lacking access to adequate healthcare or the means to escape disease-ridden areas. These disparities can lead to civil unrest and increased tensions among different classes or ethnic groups.

Culturally, pandemics have been instrumental in shaping art, literature, and music. Artists often reflect on the societal mood, capturing the despair, hope, and resilience of populations during these testing times.

Politically, the way leaders respond to pandemics can make or break their careers. Efficient handling can cement a leader’s legacy, while mismanagement can lead to widespread criticism and political upheaval. Moreover, public health measures can lead to discussions on individual rights vs. collective safety, shaping policy decisions for years to come.

Lastly, on a more personal level, pandemics can change the way individuals view mortality, health, and community. They remind us of our fragility but also our collective strength when faced with shared adversities.

In essence, the impact of pandemics on societies is multifaceted, altering the course of history in ways one could never fathom during the initial outbreak. The resilience and adaptability of human societies, however, shine through, as we continually find ways to rebuild, learn, and grow from these challenging experiences.